Attention, everyone! I am working on a new book, which I hope to finish within the next two years. It is an intellectual history from the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the present. The excerpt below is from the part dealing with the Abbasid-era translation movement centred on the city of Baghdad from the 8th century onward. If you like this excerpt from the still-developing draft of the book, or even if you don’t, let me know!

The Aristotelians of Baghdad

Islamic thought inherited the late-antique preoccupation with reconciling two competing philosophical traditions of the Graeco-Roman world. One was the school of Aristotle and the other was that of Plato.[1] Aristotelian philosophy concerned itself with many different subjects, but the approach was always the same: rational enquiry through systematic logic and reasoning from premises to conclusions. In contrast, the minds of the Platonists, and later Neoplatonists, were fixed upon the study of existence itself, or metaphysics as we now call it. Apart from Plato, his late-antique epigones Plotinus (205–270) and Proclus (412–485) loom large, and the main force of their thought was that existence was the result of an overflow or emanation from ‘the One’ — a perfect, utterly transcendent god about whom almost nothing can be known or said. Salvation meant escaping this world and returning to ‘the One’ by putting off all bodily desires and by developing the rational soul through philosophy. So it is easy to see both why an attempt at synthesis of the two schools was so tempting and why it was actually impossible. Nevertheless, the scholars of the Baghdad translation movement seemed to carry it off, albeit by accident.

By accident? Perhaps not entirely. Books IV and VI of Plotinus’ Enneads were paraphrased in Arabic and given the title The Theology of Aristotle, and Proclus’ Elements of Theology was translated and called Aristotle on the Pure Good. Ambitious translators, who wished to assure their books a reading public, may have deliberately exchanged the obscure names of Plotinus and Proclus for that of the more illustrious Aristotle. But, however it happened, both Hellenic rationalism and a substantial portion of metaphysics came into Abbasid intellectual circles as a single parcel under the name of Aristotle. And Aristotle could not really have contradicted himself (or so it seemed), even though he appears to reject Platonic ideas in some of the writings attributed to him.

The Greek luminaries came to be known as al-awwaliyun, or ‘those who came first’. Among them, pride of place went to Aristotle who was called ‘the First Teacher’, or al-muʿallim al-awwal. Such a title suggests that there would one day be a ‘Second Teacher’, and this was the epithet given to Abu Nasr Muhammad al-Farabi (870–950). Al-Farabi arose from among the devotees of Aristotle who had gathered round Matta ibn Yunus. Matta was al-Farabi’s teacher, and he plainly transmitted to his pupil his sense of intellectual universalism and rejection of relativism. Incidentally, the same influence was exerted upon Yahya ibn ʿAdi who was a disciple of both Matta and al-Farabi. Yahya was another Christian who translated Aristotle’s works on logic into Arabic from Syriac; and his defence of the doctrine of the Trinity against al-Kindi’s criticisms is a refreshing change from the formulas of the late-antique church councils, and an impressive feat of demonstrative reasoning in its own right. But Matta and Yahya were overshadowed by al-Farabi.[2]

Al-Farabi’s intellectual achievement was to fuse the principles of Neoplatonism with those of Aristotle.[3] Just as al-Kindi saw philosophy and theology as a unity, al-Farabi considered all modes of philosophical thought as essentially the same, and so for him the Platonic and Aristotelian schools expressed one and the same truth through different words. The new synthesis is set forth in his two most important books The Principles of the Views of the People of the Virtuous City and The Political Regime.[4] These works depict the ideal polity as directed by a wise philosopher-prophet, wherein the justice and balance of nature are replicated in human society. But the exposition begins not with the world of politics, but with fundamental ideas about God and the universe. For al-Farabi, God is pure mind and the First Cause of everything. As Aristotle said, every heavenly body or sphere has its own intellect, but each of these emanates and descends from God, much as Plotinus suggested. This descent proceeds from God, through all the heavenly spheres, down to the world of elemental matter. And so, the tension between the Platonic higher world of perfect, unitary forms is reconciled with Aristotle’s rejection of it, because Platonic forms are really ideas within the single transcendent mind of God, or the ‘Giver of Forms’.

But no sooner had al-Farabi’s synthesis been achieved than someone came along to dismantle it. The demolition was done by a scholar who professed a vigorous contempt for the Baghdad Aristotelians, and yet he himself resembled no one so much as Aristotle, and he clearly owes much to both Yahya ibn ʿAdi and Al-Farabi. What he produced, though, was new and distinctive, and he was to become by far the most influential mediaeval philosopher.

Ibn Sina

Ibn Sina examined the works of the Baghdad school with a critical eye, and concluded that he could do a better job at re-articulating the synthesis of rationalism and metaphysics that passed under the name of Aristotle. Ibn Sina had enormous self-confidence which very often descended into arrogance and self-congratulation. In his autobiography, Ibn Sina insults his teacher al-Natili as one who merely ‘claimed’ to know philosophy, who had no knowledge of the ‘deeper intricacies’ of logic, and who could not conceptualise problems as well as his pupil.[5] So Ibn Sina tells us that, though he was still a youth, he began to teach himself, and undertook to explain the works of Euclid, Ptolemy, and Porphyry to al-Natili. He quickly mastered medicine also, because it was ‘not one of the difficult sciences’.[6] Ibn Sina was also rather sensitive and swift to take offence. A certain scholar of Arabic by the name of Abu Mansur al-Jabban once insulted Ibn Sina by impugning his command of philology. In revenge, Ibn Sina spent three years researching the Arabic language and compiled a volume of poetry full of obscure and recondite vocabulary. The text was then bound and made to look old. Ibn Sina then had this forgery presented to Abu Mansur, simply in order to gloat over his enemy’s failure to comprehend the text.[7]

But the man who mastered philology out of spite had struggled at first with metaphysics. Ibn Sina read constantly, even long into the night, taking draughts of wine to keep himself awake as fatigue came upon him, forcing his way through every available body of knowledge. Only Aristotle’s Metaphysics defeated him. Though he had apparently read it forty times and even memorised it, or so he claimed, he could conclude only that it was ‘a book which there is no way of understanding’.[8] So it seemed until he read al-Farabi’s commentary on it, and then all was clear. Thereafter he was a confirmed metaphysician, and a rigorous Aristotelian.

Ibn Sina’s stubborn commitment to Aristotelian metaphysics could sometimes lead to absurd outcomes. Evidence for this is found in the correspondence of Ibn Sina with fellow scholar al-Biruni. The two men exchanged a series of letters covering seemingly all the scientific problems of the day — an exchange made all the more surprising by the fact that Ibn Sina was twenty years old, and al-Biruni twenty-seven, when it occurred.[9] Al-Biruni opened with a series of criticisms of Aristotle, rejecting claims that the motion of heavenly bodies was perfectly circular, that weight and mass existed only on earth, and that the earth had been made whole and complete from the beginning, and so on. Al-Biruni’s observations had persuaded him that many phenomena were not at all as Aristotle had described, and demanded to know his colleague’s explanation for those discrepancies. Ibn Sina always defers to the First Teacher.

Al-Biruni notes, for instance, that a water-filled flask would break if heated or frozen. He demands an explanation from Ibn Sina as to why boiling and frozen water would produce the same effect. Following Aristotle, Ibn Sina argues that frozen water must contract and cause the flask to collapse inward. Al-Biruni, however, conducted several experiments and found every time that the flask was shattered outward ‘like a thing that is burdened by carrying something beyond its capacity’. At this point Ibn Sina is clearly backed into a corner, and resorts to insult:

‘It would have been more appropriate if you had used gentler language for your purposes. Well, you asked the Wise One why he was so attached to the sayings of the ancients, and he answered you accordingly…it is not his fault if you failed to express yourself properly…’.

‘The Wise One’ refers to Ibn Sina, of course, and elsewhere in the correspondence al-Biruni is addressed in a contemptuous tone as ‘the Man of Logic’. There are other instances of rudeness also. Ibn Sina’s position boils down to this: Aristotle is right, and if al-Biruni cannot grasp his reasoning and my elucidations, he must be stupid. Al-Biruni remains unconvinced, calling Ibn Sina’s opinions ‘argument for the sake of argument’, ‘nothing but a semantic dispute’, and ‘pure sophistry’.

Such a rigorous devotion to metaphysics can plainly go too far. And yet it was in that field that Ibn Sina exerted his profoundest influence upon posterity through his proof for the existence of God.[10] It is a metaphysical proof, derived from reason alone without observation of the world. Ibn Sina was proud of this, as he tells us in his usual self-congratulatory way:

‘Consider how our demonstration of the proof for the First Being, his oneness, and his being free of attributes needed no consideration of anything but existence itself; nor did it need regard for his creation or his activity, even though that is proof for him. But this strategy is more secure and nobler, namely that when we regard the state of existence, existence in so far as it is existence bears witness to him, and after that he bears witness to the rest that comes after him in existence.’[11]

Ibn Sina wrote those words in one of his last works known as The Book of Directives and Remarks. But the proof which he describes had appeared first in his Kitab al-Shifa’, or The Book of Healing in English, and a version of it appears in another book with the dramatic name of Salvation from Submersion into the Sea of Misguidance. Anyway, the Book of Healing is a vast, encyclopaedic re-engineering of Baghdad Aristotelianism, its numerous volumes covering every topic originally confronted by the First Teacher. Ibn Sina’s approach is nevertheless unique. The volume dealing with metaphysics, for instance, presents the same subject matter as Aristotle, but with wholly original arguments and conclusions.[12] This is where we meet Ibn Sina’s proof of God.

Ibn Sina begins with the self-evident truth that existence is real. He then distinguishes between existents which are necessary and those that are merely possible. Something which necessarily exists would, he says, have no cause, and would be unitary and unique. In contrast, if a thing may or may not exist, then its existence is contingent, as for example offspring are contingent upon parents. The vast set of contingent existents cannot be infinite; but even if it were, there would be no way of explaining why all those contingent and merely possible things exist. So all possible and contingent things must have an external cause, or else they would not be contingent. This external cause must be essential or necessary, and it must be a being — the Necessary Being, the source of all things, or God as he is commonly called. The Necessary Being is free from potentiality and materiality, and is therefore synonymous with pure reason. He is the subject and object of his own cognition, both agent and patient, knowing all things universally, but undefiled by any intellectual commerce with the particulars of the heavenly spheres and the sublunary world.

Like the Neo-Platonists and al-Farabi, Ibn Sina described the origination of the world as a process of emanation from the Necessary Being. That process arises, he says, from the Necessary Being’s self-apprehension, without will, intention, or passion, and for whom thought and action are equivalent. The so-called First Intellect proceeds first from the Necessary Being, through whom the First Intellect apprehends itself; and by virtue of that self-apprehension, the Soul of the Outermost Heaven is generated. This process is repeated until we reach the Tenth Intellect, which governs the lowest sphere, below which is found the sublunary world in which we live.

Modern observers may be surprised that Ibn Sina’s rehashing of Neo-Platonism caught on. So-called emanationism was profoundly influential on later Islamic mysticism, and achieved maturity in the work of Shihab al-Din Suhrawardi (1154–1191) who reimagined Ibn Sina’s cosmology as the outflow of pure, immaterial light of ever-diminishing intensity from God, the Light of Lights, down to our world.[13] This system of thought would be perfected within the mysticism of Mulla Sadra (1571–1635) in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, and it still informs Sufi mysticism today.[14] Nevertheless, Ibn Sina’s proof of the existence of God would come to be much more influential, especially far afield amongst the schoolmen of Western Christendom.

Al-Ghazali

There were some problems, though. Ibn Sina’s claim that the Necessary Being knew no particulars of the sublunary world seemed to contradict the Quranic notion of an absolutely omnipotent and omniscient God, and the idea of emanation suggested that creation was a spontaneous, albeit long and gradual, process rather than a momentary act of God’s will. And the man who came along to point out those and other problems was Abu Hamid Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Ghazali (1058–1111).

The title of al-Ghazali’s most famous work, Tahafut al-Falasifa, is often translated as The Incoherence or The Collapse of the Philosophers. Its mediaeval Latin title was even more heavy-going: Destructio Philosophorum, or The Destruction of the Philosophers. This was Al-Ghazali’s masterpiece, but it was not a free-standing work. It had been anticipated by an earlier book called The Aims of the Philosophers: an exposition of the present state of philosophy, executed so ably that it was misconstrued as the work of a convinced Neo-Platonist in the mould of Ibn Sina. In the Latin West, The Aims of the Philosophers became the main introductory text or primer on the ‘Arab’ philosophers.[15] Al-Ghazali would certainly have been dismayed by this, because his purpose had not been to spread Arabic philosophy, but rather to demonstrate a perfect understanding of the arguments that he was about to demolish.

And demolish them he did. The Incoherence of the Philosophers is a vehement attack on al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, and their master Aristotle on their own turf. Sixteen metaphysical and four physical propositions are denounced and refuted as either heretical or irreligious. These included such ideas as the eternity of the world, Ibn Sina’s metaphysical proof for the existence of God, God’s self-knowledge and ignorance of particulars, and the apparent denial of the resurrection of the body.[16] The whole force of the book is not so much to denigrate the exercise of reason as to re-establish the proper place of revelation and faith amidst the more doubtful claims of logic and metaphysics. It is not true, as it is sometimes asserted, that al-Ghazali dealt a blow to Islamic philosophy from which it would never recover,[17] since philosophy and science carried on for some time after him. Nor did al-Ghazali have the last word. About a century after The Incoherence of the Philosophers appeared, a rejoinder came in the form of the so-called Incoherence of the Incoherence by the redoubtable Ibn Rushd (1126–1198).

And yet, al-Ghazali’s struggle against unaided reason and metaphysics marks the end of the heyday of Islamic philosophy and the beginning of a new and different era. He did not bring about this change, so much as embody and express it, though; and to understand this, we must turn to another of al-Ghazali’s books.

The Deliverance from Error is al-Ghazali’s intellectual autobiography.[18] Insofar as it is preoccupied with spiritual introspection and the state of al-Ghazali’s soul, the book can be compared with the Confessions of St Augustine, or the similar works of Rousseau and Kierkegaard. But its main theme is doubt[19] — doubt in the power of human reason and sensible knowledge — and so we might also compare al-Ghazali with Descartes. When it came to philosophy, the existence of God, the truth of religion, and even sensory experience, Al-Ghazali believed that he could trust neither his intellect nor his senses. Accordingly, he embarked upon a quest for absolutely certain knowledge ‘in which the object is revealed without any doubt at all’,[20] and was for a long time disappointed. That disillusionment afflicted al-Ghazali like an illness until he realised that no discourse or argument would rescue him, but only divine grace. His intellectual health recovered, as he says, through the infusion of God’s light into his heart; and this, he realised, was the only way to certainty.

What had provoked al-Ghazali’s doubts? The political and sectarian struggles of his day, which had been growing for some time, seemed to encourage or require the search for total certainty and interior, spiritual stability. The Abbasid caliphate had nearly collapsed towards the end of the ninth century, as the Caliphs fell under the sway of their Turkic praetorian guard, and a period of military anarchy followed. A gigantic uprising of slaves, known as the Zanj Revolt, occurred in 869 and was crushed only with difficulty and great bloodshed in 883. As many as five-hundred thousand may have died in the struggle. Thereafter, the authority of the Caliph began to wane, as local Iranian and Turkic dynasts asserted their independence within the lands of the old Sasanian empire. In Al-Ghazali’s time, most of the Abbasid state had come under the rule of the conquering Seljuks: a dynasty of Turkic warlords from the northern steppe, who favoured Persian language and culture. The Caliph at Baghdad ruled at their pleasure — in Gibbon’s words as little more than ‘a venerable phantom’.[21]

Al-Ghazali’s patron, Nizam al-Mulk, was vizier to the Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah. Amidst what appeared to be the advance of heresy, Nizam al-Mulk was animated by a fervour for Sunni orthodoxy, and was determined to enforce it. Accordingly, he established several theological academies throughout the Seljuk empire. One of these was at Baghdad, and al-Ghazali was its head from 1085 onwards. But, from the perspective of al-Ghazali and his ilk, the growth of heresy did not abate. And political and religious fragmentation accelerated with the assassination of Nizam al-Mulk in 1092, and the suspicious death of the Seljuk sultan Malik-Shah in the same year. Meanwhile, the Muslim world and the Roman rump state that we call Byzantium had begun to be afflicted by the upheavals and disruptions known as the Crusades.

Worse was to come when the Mongols burst out of the steppe and conquered most of Eurasia in the thirteenth century.[22] Their progress westward can be understood as a campaign of extortion and terror, attended by destruction and slaughter on a gigantic scale, though we cannot be certain of the death toll.[23] Contemporary chronicles allege that millions of people, along with cats and dogs, were massacred in each of the cities of Khurasan. They speak also of gigantic towers of skulls and vast fields soaked with blood and guts. We may be justifiably suspicious of such claims, but the huge figures and horrific images must mean that the carnage was quite unlike anything that anyone had experienced before. A final humiliation came in 1258, when the city of Baghdad was destroyed by the armies of Hülegü Khan, grandson of Genghis. The last Caliph, al-Mustaʿsim, was rolled up in a carpet and trampled to death by horses. That was the end of the Abbasid caliphate.

Al-Ghazali’s quest for certainty and interior, spiritual clarity amidst rising disorder can be understood as an attempt to synthesise two forces. One was Islamic mysticism, and the other was the emphasis on revelation. But the synthesis was not ultimately successful, since those two forces diverged irreversibly after his death. Islamic mysticism, or Sufism, became the dominant form of popular piety as the Mongols’ advanced. Purifying one’s inner spiritual life was for many the only consolation amidst the butchery and devastation of time.[24] The twelfth and thirteenth centuries were accordingly the heyday of mysticism, embodied in the poetry of Sana’i, ʿAttar, Saʿdi, and — the greatest of them all — Rumi. In contrast, after the fall of Baghdad, the apparent certainty of literalism was ascendant. And Ibn Taymiyya (1263–1328) and the Wahhabists who followed him saw themselves as the defenders of the wreckage of Islam against philosophy, science, and mysticism alike, and asserted the absolute supremacy of the revealed word of God and the sayings of his prophet.

The End of the Golden Age

The revival begun by the Baghdad translation movement came to an end, as all things eventually do. It was not a ‘sudden and disastrous atrophy’, though.[25] The Mongols themselves would soon embrace Islam and be swept into the current of Iranian civilisation under the influence of their Persian viziers. The destroyer of Baghdad, Hülegü Khan, would fall under the sway of the polymath Nasir al-Din al-Tusi, for whom he built an astronomical observatory at Maragha in what is now Azerbayjan. And there a monastery was also constructed for the Christian scholar Bar Hebraeus who carried on the tradition of Abbasid science in his lectures on Euclid and Ptolemy.

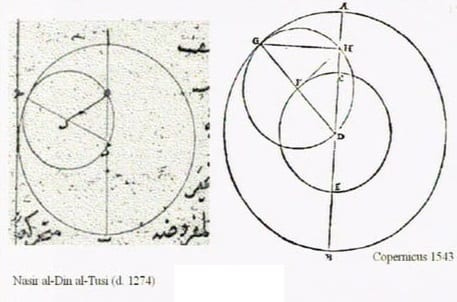

Nasir al-Din al-Tusi’s observatory at Maragha inaugurated a new astronomical school. The order of the day was to reform the model of the universe handed down from Ptolemy through Ibn al-Haytham and others. The system inherited by al-Tusi involved rather a complex mechanism, which grew ever more cumbersome after generations of tinkering to shore up the whole ramshackle structure. Al-Tusi simplified things somewhat by combining two epicycles in uniform motion — effectively a small circle rotating inside a large circle, causing a point on the circumference of the smaller one to oscillate in linear motion along the diameter of the larger one. This seemed to explain variations in the distance of the planets which we know to be caused by elliptical orbits. Anyway, the mathematical model of al-Tusi, known as the Tusi Couple, was later augmented by the other theorems of his followers al-‘Urdi, al-Shirazi, Ibn al-Shatir, and al-Khafri. And those incremental improvements somewhat simplified the Ptolemaic model and had somewhat greater predictive power. And yet, the results were still insufficient. Even the order of the planets was uncertain. The moon and the sun clearly seemed to go round the motionless earth, and Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn followed somewhere beyond the sun; but no one could agree on where Mercury and Venus were — no one, that is, until the last of al-Tusi’s followers sorted it out.

I am referring, of course, to Copernicus (1473–1543), whose great insight was to place the sun at the centre of the revolving planets; and, when he did so, suddenly the mathematics of the Maragha astronomers had near perfect predictive power, and the planets themselves fell into their proper order. The mathematics that made the Copernican system work — especially the Tusi Couple — were lifted from the Maragha school, often without acknowledgement.[26] Copernicus did not read Arabic, and exactly how he found out about the Maragha theorems is unknown, but he was certainly aware of them.

The Western debt to ‘the Arabs’ is, for the most part, better acknowledged. When the fruits of the Baghdad translation movement had reintroduced Aristotle to the West, the greatest disciple of Ibn Sina turned out to be St Thomas Aquinas, though there were many others. Later, at the height of the Italian Renaissance, Pico della Mirandola (1463–1494) opened his Oration on the Dignity of Man with an invocation of Ibn Muqaffa’.[27] Raphael’s painting of The School of Athens, completed in 1511, depicts Ibn Rushd reading over the shoulder of Pythagoras. The Flemish anatomist Andreas Vesalius (1514–1564) referred to ‘those Arabs who are now rightly as familiar to us as are the Greeks’.[28] Arabic had been taught for some time at the universities of Padua and Bologna, and other great universities were to imitate that example; and many scholars, such as Andrea Alpago (1450–1521), travelled to Damascus to learn it first-hand. And, in 1584, the Medici Oriental Press began to produce the first printed editions of Arabic medical and astronomical scholarship for an enthusiastic European audience.[29]

With the coming of the Mongols, the round city of Baghdad, like a mandala, was swept away. The old Sasanian canals and irrigation networks fell into ruin. Excessive taxation forced peasants to flee, and Iraq never recovered. The Fertile Crescent became a permanent frontier across the fragmentary world of Islam. On one side were the Mongols of Iran, and on the other the Mamluks of Syria and Egypt — a division which has lasted through the rivalry between the Ottoman and Safavid empires down to the present day. In North Africa to the west of Egypt, Berber dynasties arose. In the Iberian peninsula, Ferdinand III of Castile (r. 1217–1252) drove the Muslims out of Cordoba into Granada, and Jaime I of Aragon (r. 1213–1276) conquered Valencia. The old theory of universal monarchy was dead, and a new era of ‘sultans, khans, and kings’ had begun.[30]

When the unity of the Muslim world was gone, so was the urge to synthesise all modes of philosophy and science. Learning was hardly extinct, but centralised patronage of scholarship was over, and the spirit of intellectual freedom had abated. In the East, there would be no more nocturnal visions of Aristotle, nor debates about logic and grammar. The new Islamic regimes advertised their commitment to Islam by waging jihad, and through architecture and works of art, including illuminated Qur’ans and miniature painting. Meanwhile, the old Abbasid scientific and philosophical heritage would find a new lease of life abroad. Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, al-Ghazali, and Ibn Rushd were to become Alpharabius, Avicenna, Algazel, and Averroes. Mysterious new words would appear in the languages of Europe: alchemy, alembic, zenith, alcohol, algebra, and zero, to name a few. And the name al-Kharizmi would come to be used for any process of problem-solving or calculation: our word algorithm.[31] The stream of learning that originated in the Abbasid translation movement would soon flow west.

[1] I am following Morrissey, F., A Short History of Islamic Thought, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2022, p. 52–54.

[2] Adamson, P., Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, volume 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016, p. 55–58.

[3] Morrissey, F., A Short History of Islamic Thought, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2022, p. 92–95.

[4] For analysis of the philosophy of al-Farabi, see Adamson, P., Philosophy in the Islamic World: A History of Philosophy Without Any Gaps, volume 3, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2016, p. 67–69; 70–76.

[5] Life of Avicenna, p. 20–23.

[6] Life of Avicenna, p. 24–25.

[7] This incident is narrated in the part of Ibn Sina’s autobiography completed by one of his students al-Juzjani (Life of Avicenna, p. 69–72).

[8] Life of Avicenna, p. 32–33.

[9] For a brief summary, see Strohmaier, G., Al-Biruni in der Gärten der Wissenschaft, Reclam, Leipzig, 2002, p. 48–59. There is also an English translation prepared by Rafik Berjak at https://www.academia.edu/30512389/The_Medieval_Arabic_Era_Ibn_Sina_Al_Biruni_Correspondence.

[10] Mosrissey, F., A Short History of Islamic Thought, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 2022, p. 99.

[11] Ibn Sina, Kitāb al-ishārāt w’al-tanbīhāt (ed. J. Forget), Brill, Leiden, 1892, p. 146. My translation.

[12] For the text, see Avicenna, The Metaphysics of The Healing, a parallel English-Arabic text translated, introduced, and annotated by Michael E. Marmura, Brigham Young University Press, Provo, Utah, 2005. For a good summary of Ibn Sina’s proof of God, see Fakhry, M., A History of Islamic Philosophy, third edition, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004, p. 156–160. And for analysis, Bertolacci, A., The Reception of Aristotle’s Metaphysics in Avicenna’s Kitab al-Shifa’: A Milestone of Western Metaphysical Thought, Brill, Leiden, 2006. See especially pages 149ff.

[13] Fakhry, M., A History of Islamic Philosophy, third edition, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004, p. 303–314.

[14] Fakhry, M., A History of Islamic Philosophy, third edition, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004, p. 314–321.

[15] Minnema, A. H., The Latin Readers of Algazel, 1150-1600, doctoral dissertation, University of Tennessee, 2013 (https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2602).

[16] Consult the summary in Fakhry, M., A History of Islamic Philosophy, third edition, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004, p. 228–239.

[17] This idea seems to have originated in the nineteenth century with Salomon Munk, Mélanges de philosophie juive et arabe, A. Franck librairie, Paris, 1859, p. 382, and has resurfaced every so often since then (see, for instance, Craig, W. L., The Kalam Cosmological Argument, The Macmillan Press Ltd., 1979, p. 42).

[18] Al-Ghazali, Deliverance from Error and The Beginning of Guidance, translated by M. Montgomery Watt, Islamic Book Trust, Kuala Lumpur, 2005 (originally published in 1953).

[19] Fakhry, M., A History of Islamic Philosophy, third edition, Columbia University Press, New York, 2004, p. 224–225.

[20] Al-Mundidh min al-dalal w’al-Mawsilu ila dhi al-‘izzati w’al-jalal, Maktabat al-Haqiqa, Ihya Press, 2016, p. 3. My translation.

[21] SOURCE

[22] There is an excellent summary of rise of the Mongols in Barfield, T. J., The Perilous Frontier: Nomadic Empires and China, 221 BC to AD 1757, Blackwell, Cambridge MA & Oxford UK, 1989, p. 187–202.

[23] Morgan, D., Mediaeval Persia 1040–1797, second edition, Routledge, London and New York, 2016, p. 53–62; Saunders, J. J., The History of the Mongol Conquests, The University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia, 1971, p. 54–63; 109–112; 177–178.

[24] See Lane, G., Early Mongol Rule in Thirteenth-Century Iran: A Persian Renaissance, Routledge, London, 2003, p. 226–232 and Arberry, A. J., Aspects of Islamic Civilization: The Moslem World Depicted Through Its Literature, second edition, Ann Arbor, The University of Michigan Press, 1971, p. 16–17.

[25] Bennison, A. K., The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the ‘Abbasid Empire, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2009, p. 201.

[26] Saliba, G., Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance, The MIT Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2007, p. 193–232; Ragep, F. J., ‘Copernicus and His Islamic Predecessors: Some Historical Remarks’, Filozofski vestnik, XXV (2), 2004, p. 125–142.

[27] Pico della Mirandola, G., Oration of the Dignity of Man: A New Translation and Commentary, edited by Francesco Borghesi, Michael Papio, and Massimo Riva, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

[28] This is found in the preface of Vesalius’ On the Fabric of the Human Body addressed to emperor Charles V, which can be found online at https://www.nlm.nih.gov/ exhibition/historicalanatomies/vesalius_home.html.

[29] Jones, R., ‘The Medici Oriental Press (Rome 1584-1614) and the Impact of Its Arabic Publications on Northern Europe’ in Russell, G. A., The ‘Arabick’ Interest of the Natural Philosophers in Seventeenth-Century England, Brill, Leiden, 1993, pp. 88–108.

[30] Bennison, A. K., The Great Caliphs: The Golden Age of the ‘Abbasid Empire, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2009, p. 204.

[31] Cf. Gibb, H. A. R., Arabic Literature: An Introduction, second (revised) edition, Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1963, p. 66.